"For every measure of well-being and opportunity—from cancer rates, asthma rates, infant mortality, unemployment, education, access to fresh food, access to parks, whether or not the city repairs the roads in your neighborhood—the foundation is where you live." - House Rules, This American Life

"The segregation in America between a largely dark inner city and a largely white suburban community is not something that just magically happened from market forces. ...When the government instituted rental housing in inner cities (in the form of public housing projects) for poor minorities, and then developed home ownership in low-cost, suburban communities for low-income whites (where you could put almost nothing down) they created this incredible wealth gap." - Dalton Conley, Professor of Sociology at NYU

Redlining?

It is fair to say that most people living in the United States today are not fully aware of our country's history of redlining. Perhaps the term and practice is not even all that well understood. No problem, but we're going to change that, right now.

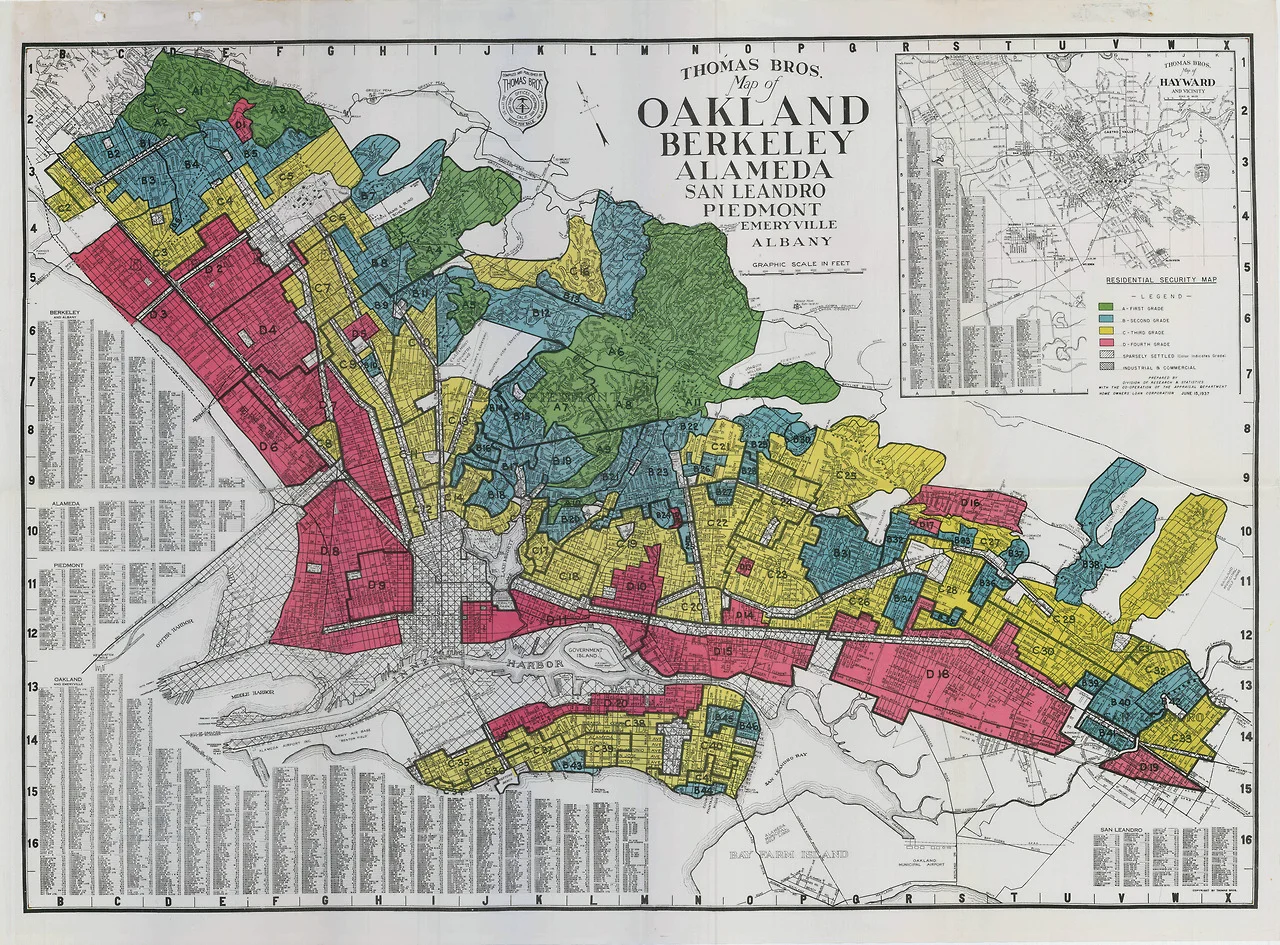

The term "redlining" was coined in the late 1960s and refers to the practice of marking a red line on a map to delineate areas (historically non-white neighborhoods) where banks were warned not to invest. The term was later extended to refer to the discriminatory practice of denying, or simply charging more for, services such as banking, insurance, health care, or food at supermarkets to particular groups of people.

Since film is such a great way to learn things, this short (6 min.) clip from California Newsreel's series Race: The Power of an Illusion provides a compelling (albeit frustrating and embarrassing) history lesson:

If you don't have time to watch the video or if you simply prefer to read, here are the key takeaways and a few extra facts:

- After WWII, new federal policies and funding initiatives (e.g. the G.I. Bill) were created to offer veterans a chance to buy single family homes at affordable rates.

- However, real estate practices and federal government regulations directed government-guaranteed loans toward white homeowners, and away from non-whites.

- The underwriters for the Federal Housing Association (FHA) warned that that the presence of even one or two non-white families could undermine real estate values in the new suburbs, and these government guidelines were widely adopted by private industry (e.g. real estate developers).

- Using this scheme, federal investigators evaluated hundreds of cities across the country for financial risk and gave the highest rating (marked by the color green) to communities that were all white, suburban, and far away from minority areas.

- Communities that were all minority or in the process of changing were given the lowest rating and were marked by the color red (thus "redlined"). As a consequence, most mortgages and loans went to suburban America, which was being developed along explicit racial lines that benefitted the white community.

- To give some staggering context, from 1934-1962, the federal government underwrote $120 billion in new housing funding. Less than 2% of this went to non-white families.

- And these decisions were most certainly avoidable: “A government offering such bounty to builders and lenders could have required compliance with a nondiscrimination policy,”wrote Charles Abrams in 1955, but “instead, the FHA adopted a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws.” (The Case for Reparations, The Atlantic, June 2014).

wealth Disparity and Home Ownership

As one might expect, the legacy of these policies can still be felt today in this country, where the net worth of the average black family is approximately 1/8 that of the average white family. And since children of families of similar income levels continue to show differences in performance and achievement, less-informed people may try to attribute these differences to something cultural or innate, when it really is fundamentally a question of longstanding and historical inequality:

"We're not comparing blacks and whites on an equal footing if we don't take into consideration these wealth differences in addition to the income differences. ... And that's what's driving these seemingly cultural or behavioral differences in the next generation ... inequality." (from An Interview with Dalton Conley, Professor of Sociology at NYU)

Policymakers also tend to focus primarily on income levels when measuring economic progress among groups, instead of looking at differences in wealth, since income rates show less disparity. In a recent paper published by the Urban Institute, the authors argue that:

"Policymakers often focus on income and overlook wealth, but consider: the racial wealth gap is three times larger than the racial income gap. Such great wealth disparities help explain why many middle-income blacks and Hispanics haven’t seen much improvement in their relative economic status and, in fact, are at greater risk of sliding backwards."

From here, one must ask: why are policymakers avoiding this conversation about wealth disparity? While there is no straightforward or singular answer, a skeptical mind could assume it has something to do with avoiding responsibility. Since our government has made many historical decisions aimed at keeping opportunities to accumulate wealth significantly farther out of reach for non-white families, it could be argued that our government is responsible for compensating for past harm, which is a provocative and charged topic. For more on this, read Ta-Nehisi Coates' article, The Case For Reparations, published last year in The Atlantic magazine.

But for now, let's look again at racial disparity since some readers might be able to skim over the term "1/8" and not fully grasp how big of a difference this is. Thankfully, for those visual learners, we have some tools to help clarify this further. Below is a graph that illustrates the rates of average family wealth split out by race and ethnicity over a 27 year span (1983-2010). Not only is the difference great, sadly it has also increased over time:

So where does this huge difference come from? As one might expect, the dramatic split in net worth of black and white families in the United States is largely based on the differences in how valuable a family's home is estimated to be (assuming a family owns their home).

The benefits of owning a home—and more so a valuable one—are many. First of all, by owning a home, a family pays less in income tax (see this guide to the benefits of home ownership from Forbes magazine). Secondly, since owner-occupied communities tend to have higher real estate value than renter communities, the property tax base is likely higher, which means local services are going to be better. This can include something as simple as free and regular garbage services and more frequent street cleaning. It can also mean superior public education, since funding for public schools remains strongly tied to the income generated from property taxes (Chetty and Friedman, 2011).

Thirdly, once a family has built equity by paying back their mortgage, they can borrow off this equity to finance other projects or pay their children's college tuition. This financial support makes it less likely that these children will have to take out and carry huge student debt, thus freeing them from common pitfalls: "Debt costs you time in savings, pushes back when and whether you can buy a home, start a family, open a small business or access capital," says Lauren Asher, the president of TICAS (from a recent article in Forbes Magazine). As a result, children of homeowners are in a strategic position to have their education paid for (even if only in part), to more easily save money, to more quickly buy their own home, and to be more likely to raise their family near good schools. This puts them in a prime position to start the cycle over again and further the divide.

Rental Markets

Just as housing discrimination continues to exist at significant rates within the real estate market, it should be no surprise that people of color are also often denied access to homes and apartments within the rental market.

To this point, the radio show and podcast This American Life devoted an entire episode—entitled House Rules—to discussing the impact and importance of where a person lives. Working closely with ProPublica reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones to illuminate the history of race-based housing discrimination in the United States, the episode's first segment details the work of an organization in NYC called the Fair Housing Justice Center.

Through in-depth research on contemporary segregation in the United States, Hannah-Jones found that "housing discrimination based on race is a lot less pervasive than it used to be ...[but] it still happens," and at higher rates than expected since bias practices have become more covert and harder to pick up on. In order to build a case against a potentially discriminatory landlord, the Fair Housing Justice Center hired testers to visit particular buildings and pretend to seek an apartment, while their conversations were recorded and compared. Since testers did not know which buildings were suspected of discrimination and which were simply part of the control group, the findings of some of the tests were quite surprising:

"It wasn't that she couldn't believe someone might have discriminated against her in enlightened New York City, but she thought of herself as very good at reading people, how they were responding to her, and she had detected nothing."

In this particular case, the person accused of bias had been very nice and the conversation was normal, with no overt red flags, making the findings all the more disturbing for this tester:

"I was surprised, and I was like, but he was so nice to me. He was cordial. He wasn't throwing me a party, but he was cordial, and he wasn't rushing me out ... When he told me nothing was available, I took him by face value. ... It's jarring. It's very jarring. ... It's hard for my brain to realize that there was nothing that I could do. And for a while I had a feeling of like, well, does that mean I'm misjudging other people in my life? You know, are there other people who don't want to be near me because I'm black? What does that mean? Am I just completely misjudging the people around me?"

Without instilling too much paranoia, this is deeply upsetting and it is hard to believe that today in New York City—a city purported to be so progressive—there is a fair chance that a person of color might be discriminated against and have no idea that he or she has been treated differently or denied access to opportunities.

Racism Without Racists & community isolation

To complicate matters further, many people who discriminate in subtle ways have no idea that they are even doing it. In his 2003 book, Racism Without Racists, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva writes about this very phenomenon: namely that the absence of overt racism has pushed people to deny and overlook their own small, everyday discriminatory decisions. With all that has been discussed in the media lately (e.g. Ferguson, Staten Island, and Cleveland), CNN recently published a piece about the way that many white people subconsciously perceive and interpret the behavior and culture of others—particularly those of racial minorities—to be fear-inducing or negative. Sadly, as we've all now learned so vividly, a person's fear-of-the-unknown can have lethal affects when it is a driving force in a confrontation.

A significant portion of this fear can be attributed to a simple lack of exposure and familiarity with people of racial groups other than one's own. This can be attributed, at least in part, to the continued lack of integrated communities in this country. From the same This American Life episode, producer Nancy Updike describes that:

"Black and white Americans still live substantially apart in this country. ... In hundreds of metropolitan areas, the average white person lives in a neighborhood that's 75% white, and their neighbors who aren't white are not likely to be African American."

Not surprisingly, this continued separation of communities along race lines can easily be traced back to discriminatory structural decisions—including redlining—that offered important opportunities only to particular communities. It is a full circle of influence, one that has been tragically under addressed in the media and among communities that can be conveniently unaware (see white privilege) (and this) (and this).

Additional Reading, Resources and Organizations

- Race: The Power of an Illusion - PBS's online companion to California Newsreel's 3-part documentary about race in society, science and history.

- Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (2003) by Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

- Segregation Now: Investigating America's Racial Divide - A ProPublica series by Nikole Hannah-Jones about the history of racial segregation in the United States.

- Urban Institute - Since 1968, the Urban Institute has worked to open minds, shape decisions, and offer solutions through economic and social policy research.

- Less Than Equal: Racial Disparities in Wealth Accumulation - An article published by the Urban Institute in April 2013 that discusses the role of "wealth" in the production of the economic gap between whites and communities of color in the United States.

- The Greenlining Institute - Founded in 1993, The Greenlining Institute is a policy, research, organizing, and leadership institute working for racial and economic justice.

- The Case for Reparations - An article published in June 2014 in The Atlantic magazine.

- Chris Rock on "wealth" versus being "rich" (*Warning* - video includes a lot of profanity.)